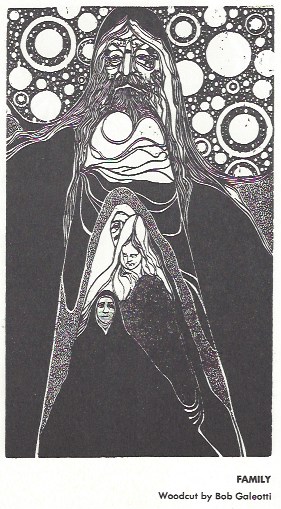

Jung once remarked that the family was like a salad. The beauty, variety and potential of this metaphor, for me, lies in the distinctiveness possible for each ingredient that can be experienced without any loss of individual characteristic. They remain delicious and harmonious in combination

with the other ingredients. The potential of difference and of the opposites comes together in this unique image of the family.

The contrast and experience of the opposites in the human is usually painful and bewildering and, according to Jung, brings “moral torment,” experienced as a crucifixion. Guggenbuhl-Craig, in his book, Marriage – Dead or Alive, comments on this torment. I quote: “If one were to dream up a social institution which would be unable to function – and which was meant to torment its

members, one would certainly invent the contemporary marriage and the institution of today’s family.” I believe some of this torment has to do with the fact that along the American way the child gets the message that if he is good, he will be happy and by late adolescence it may be demanded as a right. When it turns out otherwise, of course, he feels betrayed by life and the capacity for a new reality is lost The path to happiness is not supposed to include suffering. Secondly, the breakdown of both the extended family and certain traditional elements are crucial factors of loss.

The family seems to be in danger of losing its grip as educator, nurturer and place of refuge for its members. Jung refers to the breakdown of tradition and loss of roots as “a danger to the soul because the life of the instinct – the most conservative element in man – always expresses itself in traditional usages. Age-old convictions and customs are deeply rooted in the instincts.” Thus, if they are lost, one is severed from deep, valuable connections that would facilitate the development of t

he feeling function. Challenging and creative pioneer work is needed in each family to come to know and find ways of living personal family traditions.

The main source of torment that both Jung and Guggenbuhl-Craig emphasize, and which is my focus here, is the existence of paradoxes in the human psyche, i.e. opposites expressed at the same time within us, but most often lived out (projected) between family members. After that I will consider the value of living with this understanding.

Jung, in distinguishing himself from Freud and Adler, described his psychology as dualistic, i.e. based on the principles of opposites. Von Franz describes the psyche as a “living system of opposites.” Throughout the Collected Works, Jung emphasized the inherent paradoxical nature of man, beginning with the unconscious itself. He writes, “Thus the unconscious is seen as a creative factor, even as a bold innovator. And yet it is at the same time the stronghold of ancestral conservatism. A paradox, I admit, but it cannot be helped. It is no more paradoxical than man himself and that cannot be helped either.” In an address at a psychology conference in Zurich in 1942, he expressed, “The structure of the psyche is so contradictory or contrapuntal that one can scarcely make any psychological or general statement without having immediately to state its opposite.” In his essay on “The Function of Religious Symbols” he writes, “The sad truth is that man’s real life consists of inexorable opposites – day and night, well-being and suffering, birth and death, good and evil. We are not even sure that one will prevail against the other, that good will overcome evil, or joy defeat pain. Life and the world are a battleground, have always been and always will be, and, if it were not so, existence would soon come to an end.” Anyone who stands beyond this human experience of the opposites is literally “out of this world.”

In his Forward to Neumann’s book, Depth Psychology and a New Ethic, he states, “Life is a continual balancing of opposites, like every other energetic process. The abolition of opposites would be equivalent to death. Nietzsche escaped the collision of opposites by going into the madhouse” …But ordinary man stands between the opposites and knows that he can never abolish them.” …”the most dangerous revolutionary is within ourselves.” It is only out of the conflict of opposites that exist side by side in us that consciousness is born. Jung, in his essay, entitled On the Nature of the Psyche, finds man “simultaneously driven” to act and to reflect and describes this “contrariety in his nature” as having “no moral significance, for instinct is not in itself bad any more than spirit is good. They exist simultaneously. Negative electricity is as good as positive electricity: the psychological opposites, too, must be regarded from a scientific standpoint. True opposites are never incommensurable; if they were they could never unite – they do show a constant propensity to union –.” “Experience has amply confirmed that, in the psyche as in nature, a tension of opposites creates a potential, which may express itself at any time in the manifestation of energy. Between above and below flows the waterfall, and between hot and cold there is a turbulent exchange of molecules. “Above and below have always been brothers,” but where they meet, there will be “tumult and shouting.” In a 1929 essay in which he reconciles his views as different from Freud’s, he states, “I see in all that happens the play of opposites, and derive from this conception my idea of psychic energy. I hold that psychic energy involves the play of opposites in much the same way as physical energy involves a difference of potential, that is to say, the existence of opposites such as warm and cold, high and low, etc.”

Even more relevant, is Jung’s contention that Western culture “has never yet devised a concept, nor even a name, for the union of opposites through the middle path” – that most fundamental experience, such as Tao.” This is no easy task – no mere return to the instinct or to some element of naturalism. He claims, “Our Western superciliousness in the face of both Chinese and Indian insights is a mark of our barbarian nature, which is not the remotest inkling of their extraordinary depth and astonishing psychological accuracy. We are still so uneducated that we actually need laws from without, and a taskmaster of Father above, to show us what is good and the right thing to do. And because we are still such barbarians, any trust in the laws of human nature seems to us a dangerous and unethical naturalism.”

Warner Springs, April 29, 1978

It is vital to remember, however, that the wisdom of the Orient that acknowledges the fundamental pairs of opposites, beginning with Yin and Yang, (feminine and masculine) evolved out of their own encounters with chaos – out of massacres and power struggles – it was no intellectual effort. The awareness of Tao or the experiencing of meaning between opposites is a painful, individual, on-going task. Jung warned, in his memorial address in honor of Richard Wilhelm, close friend and translator of the I Ching, that “What it has taken China thousands of years to build cannot be grasped by theft. We must instead earn it in order to possess it. What the East has to give us should be merely help in a work which we still have to do ourselves.” In other words, these insights cannot simply be put on like a cloak, but, on the contrary, will and must lead us directly into our own individual confrontation with the opposites in ourselves and into our own humanness with all its “undercurrents and darknessess.” The same would be true for us– an intellectual grasp of the task in relation to the opposites does not spare us our own encounter with them.

Let us now consider what it might mean in a family situation if the individuals therein were to enter the chaos of the consideration of their own opposites. First of all, it is important to know that the realization and acceptance of such a task belongs to the parents, for it is specifically a problem of maturity. The struggle for the young is more a collision between outer reality and coming to terms with some infantile attitude or dependence in oneself, whereas the problem of the opposites does not really come up until a least puberty. Up until that time, the child is seldom at variance with himself and when he does run into limitations, he either submits or circumvents them. Ideally, a child needs to be helped to establish his will, his best attitude and function in order for him to be able to feel efficient and self-reliant – he does not benefit from “swinging between opposites.” Later in life, if a suspension of that will, can occur, the task of facing his opposites will emerge. The need to give the opposites complete equality can be especially acute for parents of teen-agers, because having withdrawn projections off of their own parents, that same energy comes rushing back into their own psyches and activates all that they neglected to develop earlier in life.

With willingness on the part of parents, then, to consider the paradoxes, a view of one’s own one-sidedness will emerge. One may begin to notice that all conscious attitudes are balanced by an unconscious suppression of its opposite. One may notice dreams bringing up surprising qualities or attitudes. Jung labels any such ego identification with one side of an opposite as a state of “agonizing disunion.” For example, if I am unwilling to acknowledge that I have a masculine opposite in me that exists in my unconscious, I am dangerously ego-identified with the feminine side and am off balance with myself. Here is another view of possible torment, which, if unrecognized, gets projected and lived out at the expense of family members. If I give too much of myself away to you, then I have made you too responsible for me and I am empty and dependent. Merrit Malloy has expressed this most succinctly in the following : How empty of me – To be so full of you.

A clue to this state of ego-identification with one side over another will be a state of ambivalence and irritability – always a hint of impending loss of what I will call “rudder control” of that more objective middle viewpoint and of a need for psychological distance. Furthermore, if one refuses to recognize that a compensating factor wants to come up from the unconscious to balance this one-sidedness, one literally gets into a position of defending oneself against one’s own unconscious, and as Jung describes, “he fights against his own compensating influences.” Once again, we meet another source of torment – what is actually a deep inner battle within oneself may go unrecognized as such and fall out onto someone else in the family, when you really need to have it out, so to speak, with your own inner opponent.

Without either knowledge or trust of the value of the corrective compensations trying to break through in oneself, there can be no real healing of this disunion and torment. One is thrown into an “enantiodromia,” a term from Heraclitus (pupil of Plato), “used to designate the play of opposites in the course of events – the view that everything that exists turns into its opposite.” Jung used the term psychologically to mean “the emergence of the unconscious opposite in the course of time.” In itself, it is a corrective attempt of the psyche to balance itself, but it does not lead to any union of opposites without objective discrimination from the ego— one is tossed about like a boat without a rudder, or, another image that comes to mind is a teeter-totter left to balance itself – it simply won’t balance without someone getting in the center position. With the boat rudder in hand, or, in other words, with the correct ego attitude handling the tension of the movement of that boat through the water, there is a chance of meeting whatever else may come up, either on the horizon or from down below. “Just as a chariot driver looks down upon the two chariot wheels,” so as to relate to the tension of the reins, if one can consciously carry the tension of the opposites, the possibility of being able to meet what comes up is markedly increased. It cannot be emphasized enough that the only part of us that can “hold fast” is the ego – that is its “great and irreplaceable significance.”

This experience of the ego bearing the tension happens by means of what Jung terms, the “circumambulation” i.e. holding one’s ground, often under unbearable tension between the opposites. The action of this tension is likened to that of a spiral, “if conscious mind does not lose touch with the centre,” it means something new is possible. George Doczi, Seattle architect, who focuses on patterns in nature as related to man’s psychology, has pointed out that the design of a daisy is actually formed by spirals that move in opposite directions, in other words the daisy is formed by a pair of opposites that unite or cooperate. These are important images to remember later in dealing with trusting what wants to come out of an experience of the opposites, either in oneself or within the family.

Let us now consider the probable consequences and meaning of a parent beginning to trust that the opposites in his own psyche and in his children actually exist as a means of providing regulation and balance. An individual’s own regulative authority always operates in the interests of wholeness. For me, it means that this person will recognize that, not only does he and his children have a built-in mechanism designed for their own psychological survival and balance, but that that same mechanism is also a vehicle for what wants to happen, for what wants to evolve that is new, both in the individual and between the individuals and that does unite the painful opposition in a new way.

Jung has emphasized that the conscious mind itself can’t know beyond the opposites, but that if that same ego can bear the tension of the paradox, that the unconscious psyche will “always create a third thing of irrational nature which the conscious mind neither expects or understands,” but which bridges the opposites in its own unique way, in other words, a solution comes in an unexpected form. This is the transcendent function in man, that which enables a transition to a new attitude, certainly a lecture in its own right, but here I believe it is especially important in relation to the family to know that life itself has provided for us a way to deal with the reality of the opposites encountered here. The realization of being able to bear that “circumambulation” and trusting that one does have the possibility of the transcendent function coming to one’s aid, leads one to an experience of the Self. Von Franz described this as “an inner certainty, peace and sense of meaning and fulfillment,” a certain self-acceptance and self-reliance that enriches those around us. One feels on solid ground with oneself. A French analyst, George Verne, grandson of Jules Verne, science fiction writer, poses a stark question, “What if this emergence of the unexpected, and the unsusceptible were in reality the ultimate archetype of life, its immediate and profound authenticity?”

So, whether we choose to see the opposites and their effects or not, they will be there, within ourselves and between each other. What is denied in consciousness will become powerful at an unconscious level. The type and attitude differences will plague us, the effects of the inferior function or attitude when it comes up will be disruptive and disturbing. Any conscious acceptance of a repressed function has been described experientially as “equivalent to an internal civil war:” the constant birthing and dying of each individual’s growth process continues whether we relate to it or not, health and illness will come and go and interrupt us; the individual rhythms of each person will not harmonize; the male-female differences will add their zestful effects; the realities and expectations of the world and the realities and expectations of the soul will clash; the need to be alone, to be an individual, and the need to be part of the group will co-exist in us; the need for containment will argue with our requirements for independence and creativity; the need to construct and the need to destruct, neither will be denied; the desire to share will argue with the desire to withhold – all must be lived – but, perhaps most difficult and most paradoxical of all, knowing when to know, when to take the responsibility and to act will argue with when to doubt, when to be open to the unknowable, to chaos, to madness, to the unexpected and to what wants to emerge.

Assuming then that the psyches of the individuals in a family are essentially at cross purposes with themselves and that that will pretty consistently be projected out onto each other, why bother having a family? More and more people ponder that question today. I believe Eleanor Bertine speaks to this dilemma most clearly. She writes: “Individuation cannot take place in a vacuum. As Dr. Jung once said, ‘The hermit either will be flooded by the unconscious or he will become a very dull fellow.’ Life must be lived to the full if it is to change anyone for the better. It is possible to develop a certain amount of consciousness in relation to things and inanimate nature and even more in relation to animals, where feeling may be strongly touched. But only another human being can constellate so many sides of ourselves, can react so pointedly, and can bring to consciousness so much of which we had been unaware. And because of the real values involved, and consequently the deep desires, the heat of emotion is raised high enough to produce the transformation more readily and more often in relationship than in almost any other experience in life.” Guggenbuhl-Craig believes that family structure is instinctive for some animals, but that among humans it is only “the product of human effort.”

The question regarding this human effort becomes – what is required to endure the heat of relationship and therefore, of paradox? In his essay on The Psychology of the Transference Jung lists some specific virtues that he considers vital to analytical work. I believe they are also extremely relevant to family life. These values are “endless patience, perseverance, equanimity, knowledge, ability and capacity for suffering.”

I would like to amplify these further, both from my practice experience and from my own personal family life. Regarding what is important to know, among other things, I would say:

Please know that any time opposites clash, whether in yourself or with another person that there may be shouting, disorientation, confusion and a lowering of consciousness to threatening proportions. The dialogue between the opposites is neither polite nor kind. It is experienced much more as a devastating ordeal which was not freely chosen, but which you, none-the-less find yourself immersed in. There will be tension and pain. Conflict cannot be circumvented.

Know that as soon as opposites are recognized that both are immediately relativized. One can then move from the torment of one-sidedness to the torment of an ethical decision.

Know that your dreams are trying to inform and balance you.

Know that there are no rules to cope with the paradoxes of life.

Know that if the opposites aren’t too far apart that humor can bring them together. We can begin to laugh when we see that the opposite is also true.

Remember that manners and respect are important manifestations of the feeling function, and will always facilitate an improved relationship to the opposites, whether in yourself or with others.

Know the importance of space. There is not enough recognition or value given to the desire and need to be alone within a family. Can you trust the cocoon time of another person without feeling left out or rejected or without having to intrude into that cocoon where growth and balancing and the struggle for psychological honesty can happen?

Know that compromise and sacrifice will be required by everyone at some time or another and not necessarily at the same time.

Know that being able to listen actively and wholeheartedly to someone in your family is the only way to fully recognize and relate to on-going change, but know also that it will happen whether you listen or not.

Remember that the psychic decision-making apparatus in each family member will be very individual, and will not synchronize regularly with anyone else. The individual is his own most important resource.

Know that as a parent, how you live and how you do not live, what aspirations you fulfill and what you neglect in yourself will influence your children profoundly. Know the danger of neglecting your own development, for then the family begins to be perceived as growth-stunting.

Know that personality is a seed that only develops very slowly throughout life, Don’t expect a child to be either mature or whole. It seems to have been Jung’s hope that a parent might appreciate a sense of being involved with “the mysterious evolution of the highest human faculties.” Frank Lloyd Wright once remarked, “Mothers are architects of human beings…Be careful.” The mother, indeed, will set the emotional atmosphere in the home.

So, the question arises, “How do you help a child save his own soul?” especially when his pathway is different from your own. What the Self demands of that child may be in direct opposition to your expectations and needs. Such a problem is evidenced in the tragic remark of a father to the therapist regarding his 20 year-old son, “I didn’t want my son free – only well.”

Now, I would like to focus briefly on abilities and then approach equanimity and patience. If I were to choose one ability outside of a serious willingness to listen to each other, it would be an individual’s willingness and increasing ability to process information, i.e. to be able to sift or filter, not only what comes towards him at an outer level, i.e. the situational factors, but to become aware also of what comes up from an inner level, ( I call it the “inner committee” ) before a response is released. Such processing would also include consideration of how much or what part of the presenting situation belonged to one or not. In other words, is this mine or yours, or, if both, what part is mine and what part is yours? Jung speaks of this lack of regard for circumstances in The Vision Seminars as “primitive.” Jeanne Palmer, psychiatrist and analyst, in her article on Relationship, seems to equate what I call processing with a sense of free will that is available to us as a means of reorientation from our own conditioned responses that may be inappropriate, ineffective or harmful. In Jungian terms, I might add that such processing would ideally include conscious consultation with all four of one’s functions, which are then consciously lived through Eros.

According to Sheldon Kopp, New York therapist, such personality development will cost you “your innocence, your illusions and your certainty.”

Perseverance, patience and equanimity, for me, describe a certain element of composure and evenness of mind that one hopes for in trying to reach a place of impartial judgment in oneself and a certain tolerance of ambiguity. I believe these qualities are the necessary background for being able to hear feedback from each other in a family, and to hear it as just that. Children know parental weak spots. Only if parents can be open and allow such news of themselves to be just that, news, without blaming or becoming too annoyed, can a child begin to learn how to criticize and to facilitate others, as one family member put it, “hopefully, with some grace.” In other words, do we not have the task of helping children learn how to encounter us, how to be correctly assertive? The question becomes, Can I trust what you tell me about myself? Or will it be too full of projections that you are unwilling to look at? Can I question you without excessive, defensive interference on your part? Is this a place where I can lose my way or stumble around or cry and still be known, loved and respected? Can you deal with my anger and my depression and my pain without contagion or fear or annoyance? Can you tolerate my struggle to formulate my ideas and express myself when they’re not coming out quickly or smoothly? Merrit Malloy expresses her struggle with this in her poem entitled, Inevitable

“When I feel I have to talk

It’s like when I have to sneeze

And know that I will

But can’t

So if I say I have to talk with you

Then can’t

Please don’t get angry

Give me time……Ah-choo!

Lastly, Jung emphasized a capacity for suffering. He quotes an untraceable source in the Ramayana, which says, “This world must suffer under the pairs of opposites forever.” According to Von Franz, he also “liked to quote Thomas a Kempis to the effect that suffering is the horse which carries us fastest to wholeness.” In my own counseling work, I find this ego capacity to suffer psychologically to be a strong indicator of just how far an individual can go with himself. Being able to suffer means being able to tolerate the pain of your own or another’s growth process, whatever that may require, with or without needing to interfere or being afraid. It means taking risks and being able to allow others to take risks; it means suffering one’s own one sidedness and inferior and shadow parts of one’s personality; it means being able to let go of what you have created, be it “a child, a work of art, a method, a situation where you are recognized or a string of words that work” so that something new can emerge; it means admitting that I am the one who needs “all my patience, my love, my faith, and even my humility, and that I myself am my own devil, the antagonist who always wants the opposite in everything. Can we ever really endure ourselves?” Jung asks.

It would seem to be Jung’s hope that in being able to face the opposites in ourselves, in allowing them to play their full part in our lives, however difficult this may be, in allowing the unconscious to express itself, whether it be through “word” or “deed, worry or suffering,” giving it consideration, without giving in too much to it, that we can at least begin to be less “in perpetual flight from ourselves.”

I am keenly aware that the conscious confrontation with the tension and complexity of the opposites within a family requires a highly developed and differentiated psyche. Paradoxically, of course, the more opposites an individual will attempt to relate to and balance, the stronger and more differentiated he or she will become, for it is only in that heat that a higher consciousness is built. The incredible beauty of what can form from such a high state of tension between a pair of opposites is available to us in the physical structure of the Notre Dame of Paris. Jung challenges us to the psychological parallel of that image.

In a letter to Rev. David Cox, Jung wrote that if man was to survive at all that he must understand the union of the opposites that “this is the task left to man.” The psychological rule is “that when an inner situation is not made conscious, it happens outside, as fate. So if an individual remains undivided and does not become conscious of his inner opposite, the world around him must “act out the conflict and be torn into opposing halves.” Such a tension can expand us or shatter us. Any truly creative family life must have the collaboration of both conscious and unconscious amidst the paradox. Perhaps what is ahead for us all is nothing but what our own light creates.

All Rights Reserved

Loci S. Yonder

Carl Jung, Vol 16, pg. 189

Guggenbuhl-Craig, Marriage – Dead or Alive, pg. 9-10

Jacobi – need book pg 90

Carl Jung, Vol. 16, pg 98

Maria-Louise Von Franz, Myth in our Time, pg. 97

Carl Jung, Vol. 16, pg 34

Carl Jung, Vol. 16, pg 76

Carl Jung, Vol. 18, pg 245-246

Carl Jung, Vol. 18, pg 620

Ibid

Carl Jung, Vol. 7, pg 76

Carl Jung, Vol. 8. Pg 206-207

Carl Jung, Vol. 10, pg. 414

Ibid, pg 484

Ibid

Carl Jung, Vol. 4, pg 337

Carl Jung, Vol. 7, pg. 205

Carl Jung, Vol. 6 pg. 213

Secret of the Golden, p. 144

Ibid

Carl Jung, Vol. 7, p. 59

Carl Jung, Vol. 8, p. 391

Earle, p. 5

Carl Jung, Vol. 6, p.109

Merrit Malloy, p. 33

Carl Jung, Vol. 3, p. 198

Carl Jung, Vol. 7, p. 82

Carl Jung, Vol. 3, p. 208

Carl Jung, Vol. 6, p. 425-426

Ibid, p. 426

Carl Jung, Vol. 18, p.711

Carl Jung, Vol. 6, p. 196

Carl Jung, Vol. 9, p. 319

Carl Jung, Vol. 12, p. 145

Ibid

Doczi, p. 76

Whitmont, Ind. and Group, p. 135

Carl Jung, Vol. 2, p. 86

Jacobi, p. 98

Maria-Louise Von Franz, p. 74

Verne, Individuation and the Emergence of the Unexpected, p. 33

Carl Jung, Vol. 6, p. 77

Philips, p. 292

Guggenbuhl-Craig, Marriage – Dead or Alive, pg. 9-10

Carl Jung, Vol. 66, p. 190

Carl Jung, Vol. 10, p. 484

Von Franz, p. 172

Carl Jung, Vol. 18, p. 625

Carl Jung, Vol. 5, p. 54

Carl Jung, Vol. 17, p.54

Carl Jung, Vol. 7, p. 170

Carl Jung, Vol. 17, p. 54

Malloy, p. 64

Kramer, Family Clinic, p.23

Jung, The Vision Seminars, p. 442

Sheldon Kopp, p. 6

Merrit Malloy, Inevitable p. 125

Carl Jung, Vol. 6, p. 197

Maria-Louise Von Franz, p.115

Carl Jung, Vol. 17, p. 36

Carl Jung, Vol. 16, p. 305

Carl Jung, Vol. 16, p. 304

Fordham, p. 104-105

Carl Jung, Vol. 18, p. 735

Carl Jung, Vol. 18, p. 71

Ibid

Carl Jung, Vol. 9i, p. 319